Definition: Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a disease that results from acquired mutations in the phosphatidylinositol glycan complementation group A gene (PIGA), an enzyme that is essential for the synthesis of certain membrane-associated complement regulatory protein

Typical Clinical Triad: Intravascular hemolysis, Bone marrow failure, and propensity to Thromboembolism

History and Epidemiology: first described in the 18th century. It is a rare disease, with a worldwide prevalence estimated in the range of 1–5 cases per million regardless of ethnicity; an increased prevalence is reported in some regions which also harbor higher incidence of aplastic anemia (eg, Thailand and some other Asian countries)

Unique feature: only hemolytic anemia caused by an acquired genetic defect

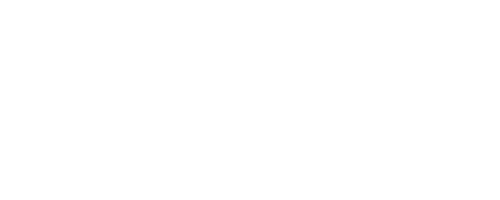

Pathophysiology:

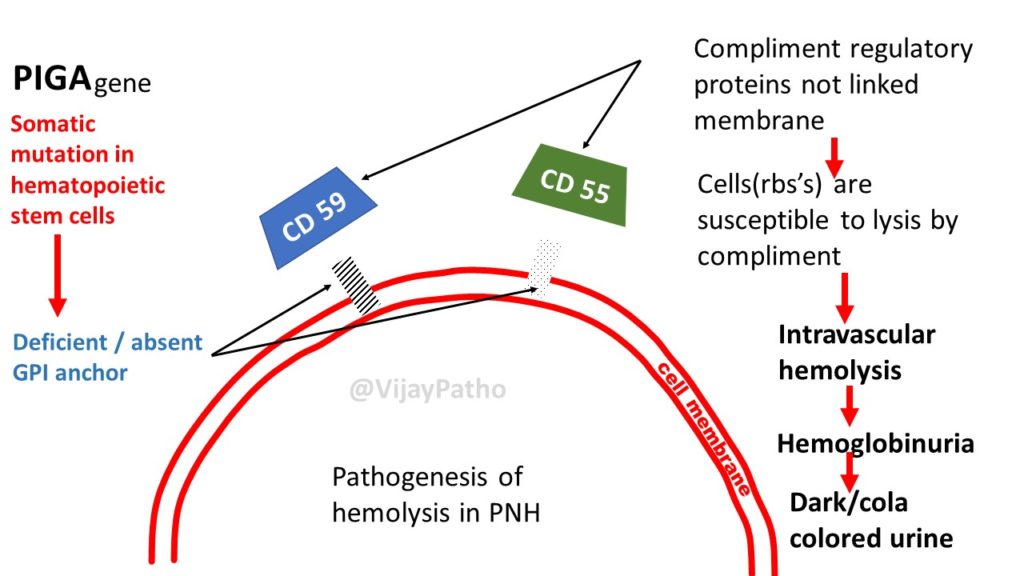

Somatic mutation in the Phosphatidylinositol glycan complement group A gene(PIGA gene)

[Cause: PIGA is X-linked and subject to lyonization (random inactivation of one X chromosome in cells of females) leading to a single acquired mutation in the active PIGA gene of any given cell]

↓

Deficient specialized phospholipid called glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) linked protein in a hematopoetic stem cell

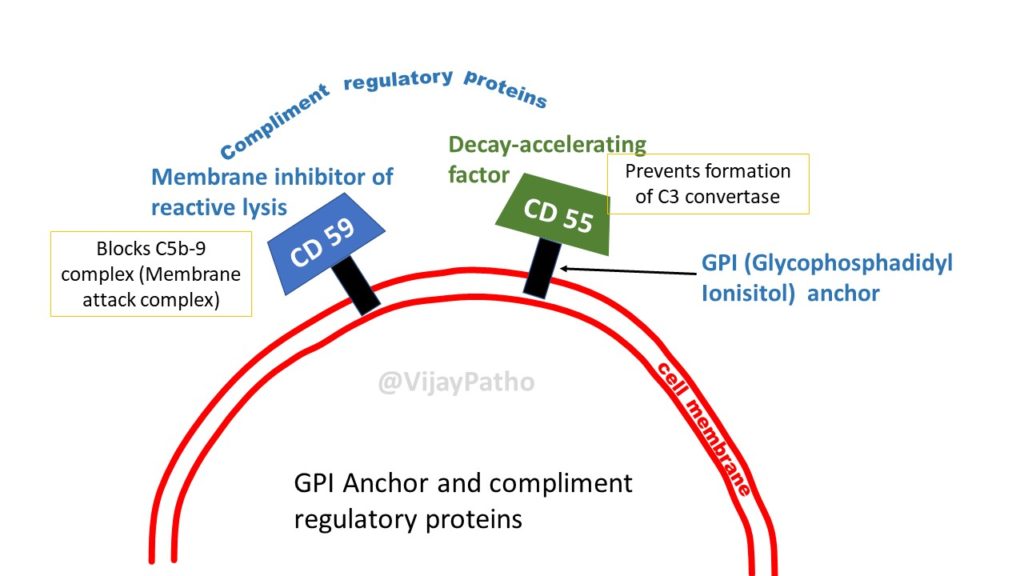

PNH blood cells are deficient in three GPI-linked proteins that regulate complement activity:

(1) Decay-accelerating factor or CD55

(2) Membrane inhibitor of reactive lysis or CD59

(3) C8-binding protein.

↓

Red cells deficient in GPI-linked factors are abnormally susceptible to lysis or injury by complement

(caused C5b-C9membrane attack complex)

↓

Intravascular hemolysis

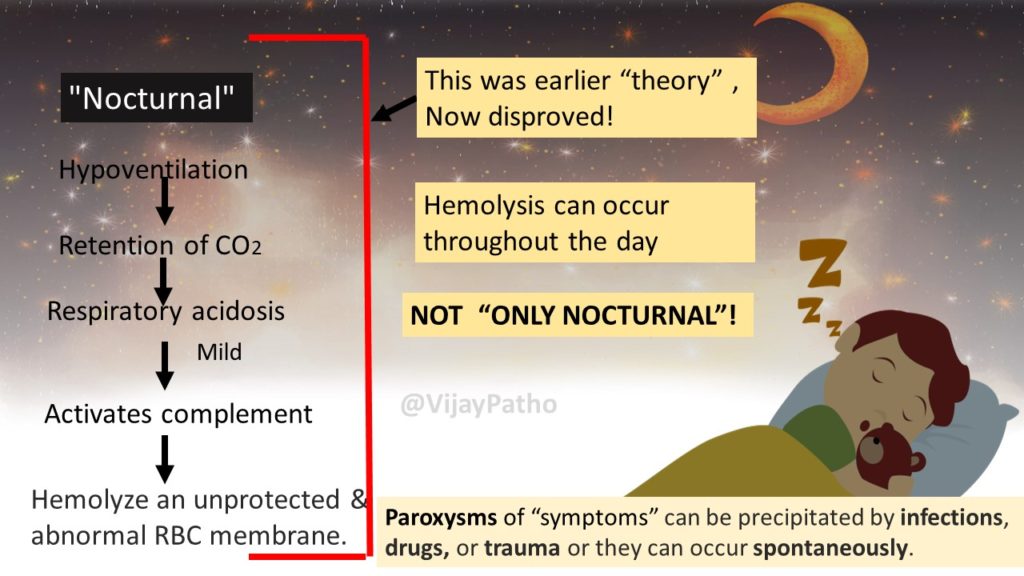

• The hemolysis is paroxysmal and nocturnal in only 25% of cases.

• Chronic hemolysis without dramatic hemoglobinuria is more typical.

• The tendency for red cells to lyse at night is explained by a slight decrease in blood pH during sleep, which increases the activity of complement. but this theory is disproved now! Hemolysis can occur throughout the day.

• The anemia is variable but usually mild to moderate in severity.

Paroxysms of “symptoms” can be precipitated by infections, drugs, or trauma or they can occur spontaneously.

• The loss of heme iron in the urine (hemosiderinuria) eventually leads to iron deficiency, which can exacerbate the anemia if untreated.

Thrombosis: How complement activation leads to thrombosis in patients with PNH is not clear

The two existing hypothesis are;

1. The absorption of Nitric oxide by free hemoglobin may be one contributing factor

2. Endothelial damage caused by the C5-9 membrane attack complex

Bone marrow failure: Most normal individuals harbor small numbers of bone marrow cells with PIGA mutations, identical to those that cause PNH. It is hypothesized that these cells increase in numbers eventually leading to autoimmune reactions against GPI linked antigens leading to marrow failure

About 5% to 10% of patients eventually develop acute myeloid leukemia or a myelodysplastic syndrome, indicating that PNH may arise in the context of genetic damage to hematopoietic stem cells.

When to suspect PNH:

1. Patients with Coomb’s negative intravascular hemolysis, especially if concurrently iron deficient

2. Patients with hemoglobinuria

3. Patients with venous thrombosis involving unusual sites (mesenteric, hepatic, portal, cerebral or dermal veins and patients with otherwise unexplained Budd-chiari syndrome)

4. Patients with unexplained refractory anemia

Laboratory Diagnosis:

Highly recommended and diagnostic tests:

1. Flow cytometry – most sensitive as well as specific

CD59 and CD55 are the most commonly assessed. The presence of any CD55/CD59 – double negative hematologic cells is considered positive for PNH

2. Fluorescent labeled aerolysin (FLAER): PNH white cells are resistant to FLAER because they lack GPI anchor on their surface

Other Tests:

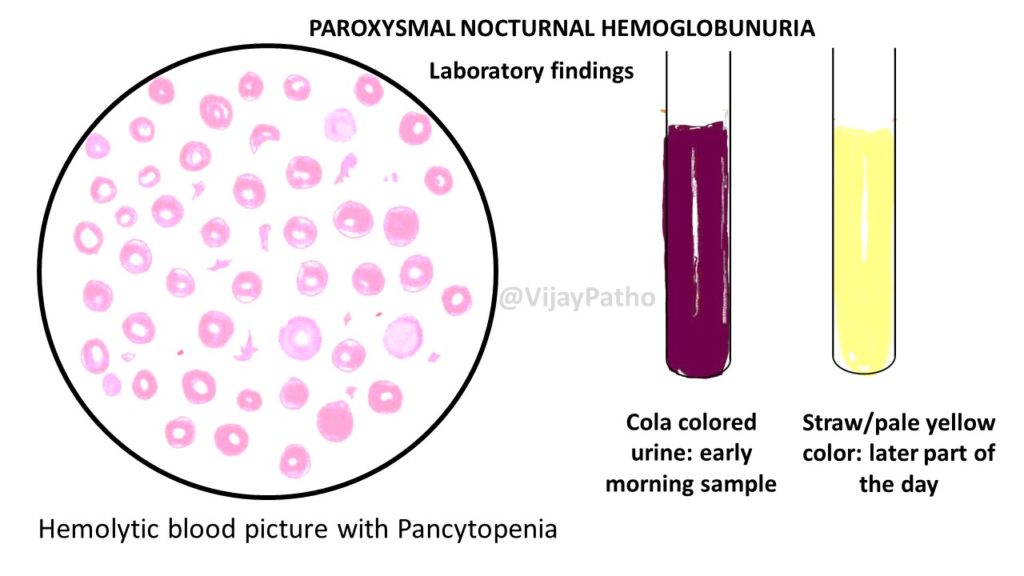

1. Peripheral smear showing macrocytic RBCs evolving into a microcytic with evidence of hemolysis

WBC show marked leucopenia

Platelets show moderate to severe thrombocytopenia

2. Reticulocytes are increased, but not commensurate with the degree of Anemia

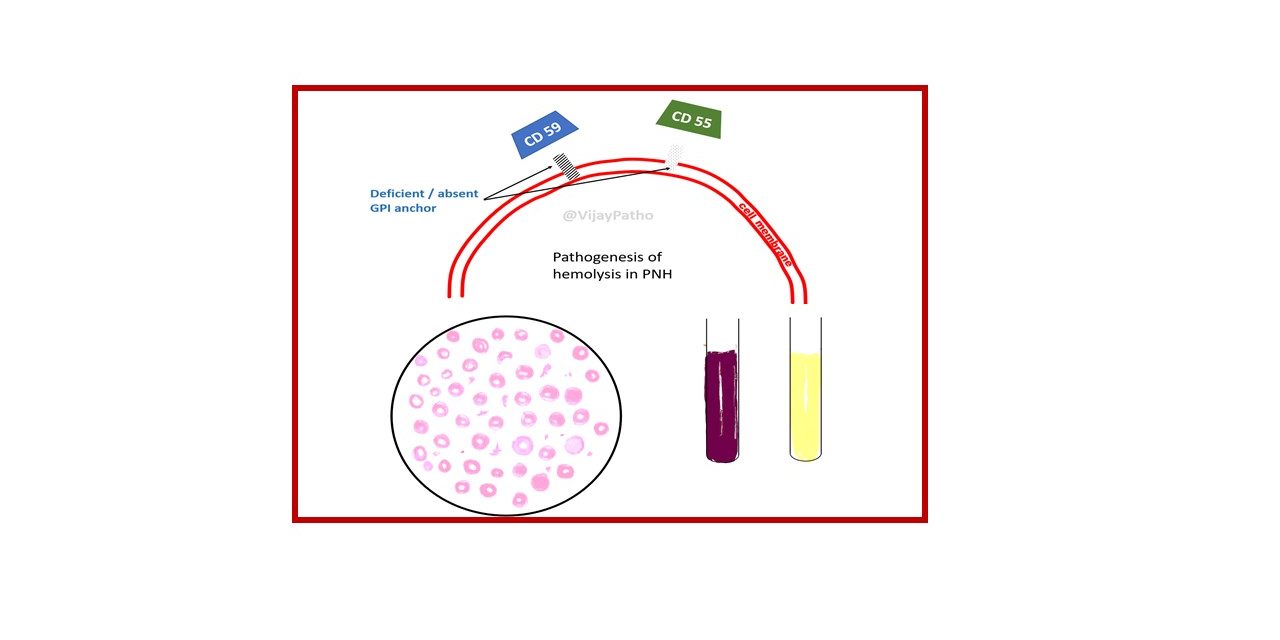

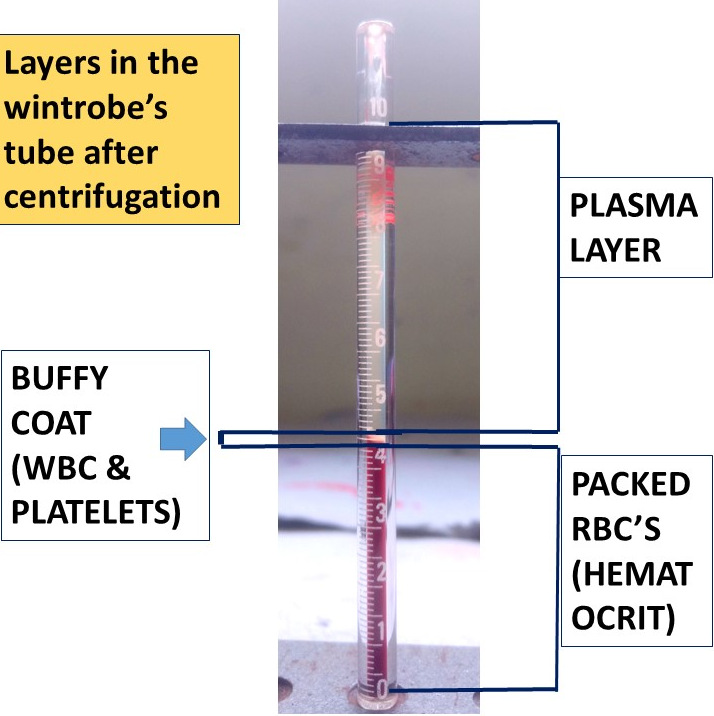

3. Bone marrow(usually not indicated): normoblastic hyperplasia

4. Direct Coombs test: negative

5. Haptoglobin levels: reduced

6. Serum iron and ferritin: decreased

7. Liver function tests: increased unconjugated bilirubin, normal AST, ALT and alkaline phosphatase

8. LDH: increased

9. Urinalysis: Hemoglobinuria, hemosiderinuria, absence of intact RBCs in urinary sediment

Watch the video tutorial on Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria by clicking on the link below

Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria

Recent Comments