What is Type III hypersensitivity?

Type III hypersensitivity, also known as immune complex hypersensitivity, is an immune response that involves the formation of immune complexes (antigen-antibody complexes) usually in the circulation. These immune complexes can deposit in blood vessels, leading to activation of complement, inflammation, and tissue injury.

In Type III hypersensitivity, the antigens are free-floating or soluble in the blood, unlike in Type II hypersensitivity, where the antigens are cell-bound or attached to tissue surfaces.

Where do immune complexes tend to deposit, and what conditions can this lead to?

Immune complexes often deposit in organs where blood is filtered at high pressure, such as kidneys and joints. This can lead to conditions like glomerulonephritis and arthritis, as well as vasculitis.

What is an example of a systemic immune complex disease?

A prototypical systemic immune complex disease is serum sickness, which can be acute or chronic. Acute serum sickness occurs after exposure to a large amount of antigen, while chronic serum sickness is due to repeated or prolonged antigen exposure, such as in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

What is the Arthus reaction?

The Arthus reaction is a type of local immune complex disease named after Maurice Arthus. It’s a localized tissue necrosis resulting from acute immune complex vasculitis, typically observed experimentally after repeated exposure to an antigen.

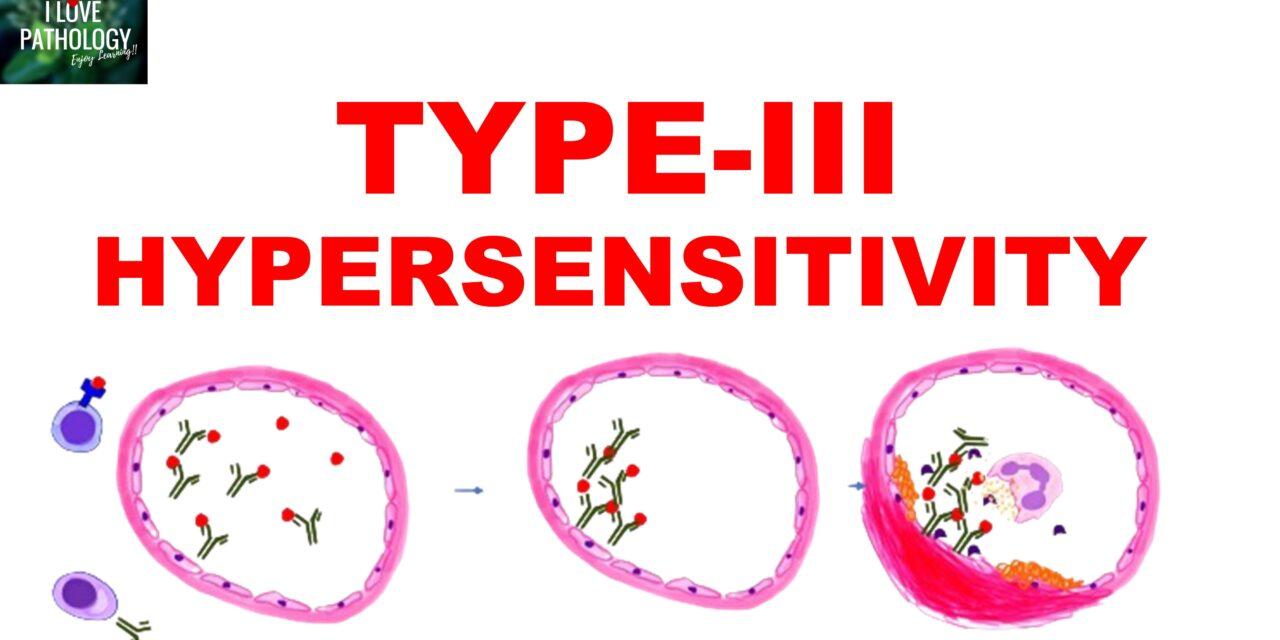

What is the pathogenesis of Type III hypersensitivity?

The pathogenesis of Type III hypersensitivity involves a series of steps leading to tissue injury as illustrated below

Formation of Immune Complexes: This initial step occurs when antigens enter the bloodstream and encounter specific antibodies, forming antigen-antibody complexes.

Deposition of Immune Complexes: These complexes, particularly of medium size, are the most pathogenic and can deposit in tissues such as blood vessel walls, kidneys, and joints.

Inflammation and Tissue Injury: The deposited immune complexes trigger an inflammatory response, attracting neutrophils and activating the complement system, which leads to tissue damage.

What determines the pathogenicity of immune complexes?

The size and amount of immune complexes play critical roles. Medium-sized complexes are particularly likely to deposit in tissues and are not cleared as efficiently as smaller or larger ones, making them more pathogenic.

Immune complexes activate the complement system, which in turn leads to the recruitment of inflammatory cells like neutrophils. These cells release enzymes and reactive oxygen species, causing tissue damage.

What is the evidence of complement involvement in tissue injury in Type III hypersensitivity?

The presence of complement proteins at the site of tissue injury and a decrease in serum complement levels, such as C3, during active disease stages suggest complement consumption and involvement in tissue injury.

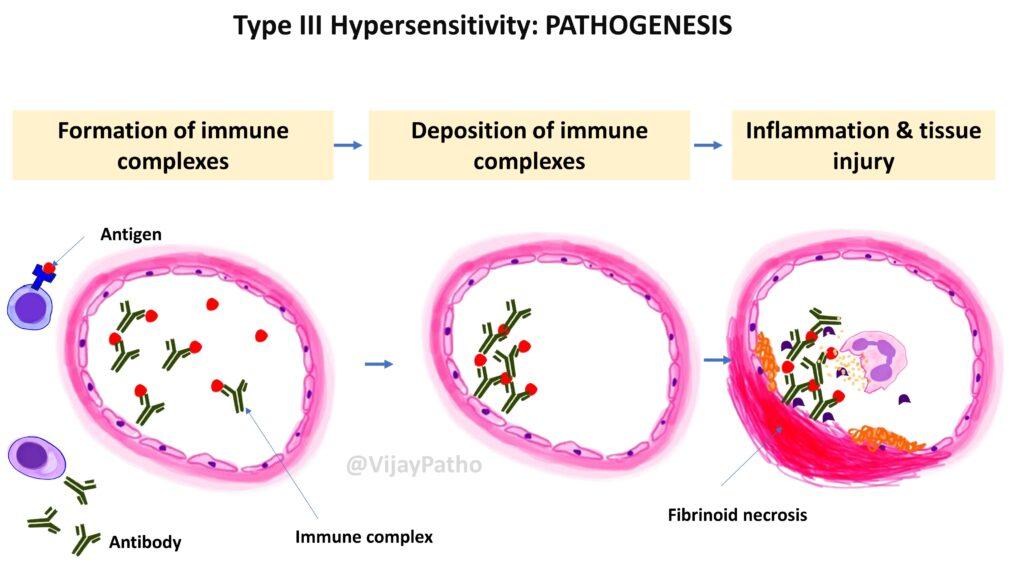

What is ‘fibrinoid necrosis’ observed in Type III hypersensitivity?

Fibrinoid necrosis refers to a type of tissue damage seen in immune complex-mediated injuries. It appears as a smudgy, bright eosinophilic area on histological examination and is a hallmark of acute vasculitis caused by immune complexes.

Give some clinical examples of Type III hypersensitivity reactions?

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): Where nuclear antigens are involved.

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis: Involving streptococcal cell wall antigens.

Polyarteritis nodosa: Often associated with Hepatitis B virus antigens, leading to systemic vasculitis.

Reactive arthritis: Where antigens from bacteria such as Yersinia can trigger joint inflammation post-infection.

You can solve practice sessions on type II hypersensitivity reaction from the link PRACTICE SESSION

Click here to watch video tutorial