Define Necrosis:

Necrosis is a process of localized cell death followed by the degradation of tissue by hydrolytic enzymes. It is characterized by the inability of the cells to maintain membrane integrity, leading to the leakage of cellular contents that elicit an extensive inflammatory reaction.

Necrosis is always accompanied by an inflammatory response, in contrast to apoptosis, where membrane integrity is preserved, and there is no accompanying inflammatory reaction.

What is the Mechanism of Necrosis:

The mechanism of necrosis involves two key processes:

a. Denaturation of intracellular proteins and

b. Enzymatic digestion of the cell.

Denaturation of proteins disrupts their normal function, leading to cellular dysfunction and death.

Enzymatic digestion is primarily facilitated by lysosomal enzymes, which are released from the lysosomes within the dying cells themselves or from surrounding inflammatory cells.

What are the key morphological changes observed in necrotic cells?

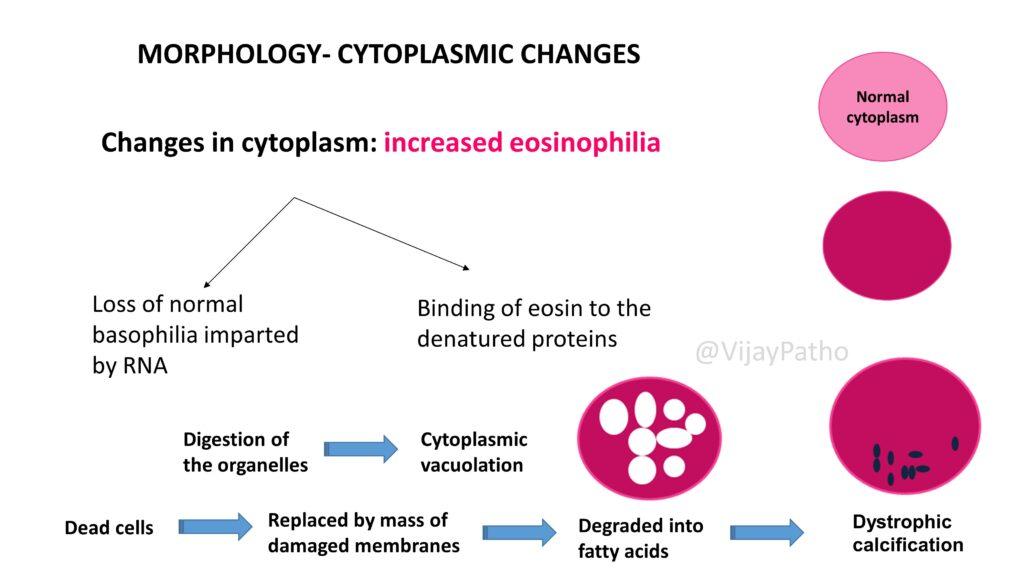

In necrotic cells, morphological changes include increased eosinophilia of the cytoplasm, cytoplasmic vacuolation, and dystrophic calcification.

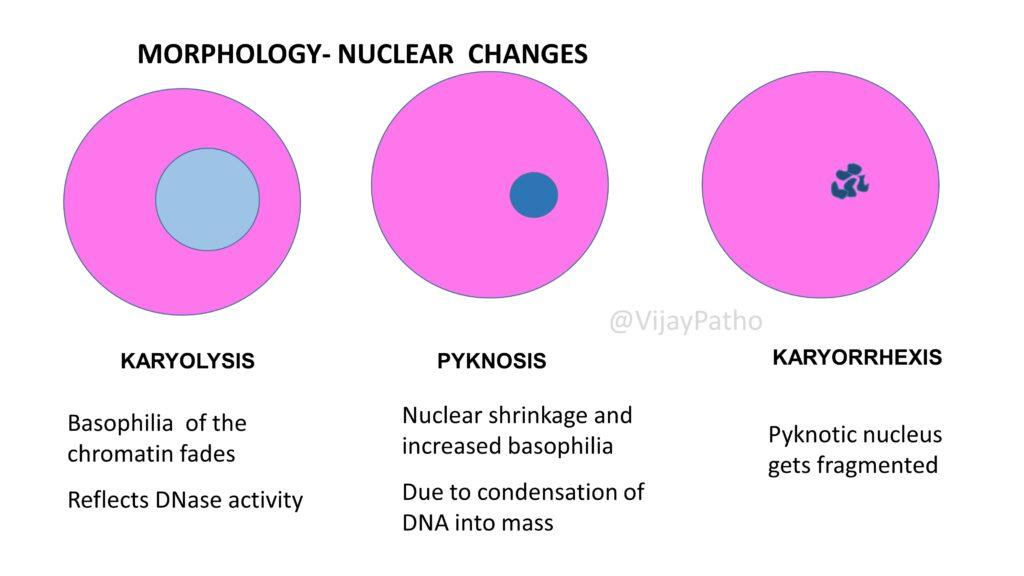

Nuclear changes involve karyolysis (fading of chromatin due to DNase activity), pyknosis (nuclear shrinkage and increased basophilia), and karyorrhexis (fragmentation of the nucleus).

Describe the different types of necrosis and give examples for each?

Coagulative Necrosis: This is the most common type of necrosis, often resulting from the sudden cessation of blood supply (ischemia) to an organ or tissue.

It primarily affects the heart, kidneys, and spleen.

The affected tissue appears firm, pale, and swollen in the early stages, turning softer, yellowish, and shrunken as it progresses.

Microscopically, coagulative necrosis is identified by the preservation of cell outlines (tombstone appearance) but with loss of nuclear detail.

Liquefactive Necrosis: This occurs due to ischemic injury to the brain or bacterial/fungal infections, leading to the formation of abscesses.

The necrotic process involves the complete digestion of dead cells, resulting in a liquid, viscous mass.

It is characterized by the transformation of the tissue into a soft, liquid substance due to the action of hydrolytic enzymes, which is particularly evident in the CNS where the brain tissue turns into a fluid-filled cavity.

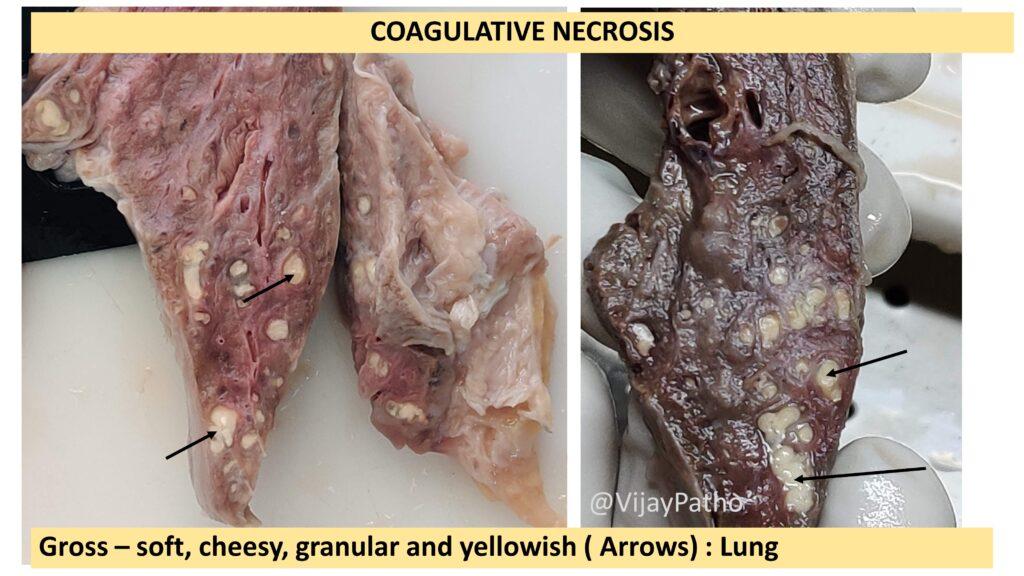

Caseous Necrosis: Characteristic of tuberculosis infections, this type of necrosis presents a cheese-like appearance of the affected tissue. Microscopically, caseous necrosis appears as eosinophilic granular debris without a discernible cellular structure, typically surrounded by granuloma comprised of epithelioid histiocytes, lymphocytes, and multinucleated giant cells.

Fat Necrosis: This type of necrosis specifically affects fat tissue and can occur due to trauma (such as in the breast) or enzymatic action (as in acute pancreatitis).

In traumatic fat necrosis, the fatty tissue is damaged directly, while in enzymatic fat necrosis, pancreatic enzymes digest the fat cells, leading to the release of triglycerides and fatty acids. These fatty acids then bind with calcium to form chalky white deposits known as saponification.

Fibrinoid Necrosis: Typically occurring in blood vessels, fibrinoid necrosis is associated with immune-mediated conditions, such as vasculitis or hypertension-induced vascular damage. The affected vessels show deposition of fibrin-like material in the wall, leading to a bright eosinophilic (pink) staining during histological examination. This material is composed of plasma proteins, including fibrin, that escape from the bloodstream into the vessel wall, causing thickening, and sometimes occlusion, of the vessel and leading to further tissue damage.

CLICK HERE to watch the Video tutorial on Necrosis

Recent Comments